The good news is that, being a blog about history, the existing material can never truly go out of date. So please browse the archives.

Thanks, and Go Frogs!

Dedicated to the history of the college game

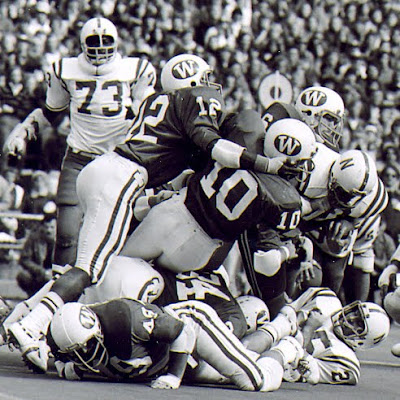

Wisconsin had not even appeared in the AP poll since mid way through the 1963 season. The early ‘70s were not halcyon days in Madison. Under the tutelage of John Jardine, a former Purdue offensive lineman who never held another head coaching job, Wisconsin continued a woeful run of form. From 1964 through 1973 under three different coaches the Badgers had posted a woeful 34-74-5 record, including two winless seasons in 1967 and ’68. In eight seasons from 1970 to 1977 Jardine went 37-47-3. The Badgers' eventual 7-4 record in 1974 would be his only winning year. Wisconsin did not make a habit of beating anyone in those days, least of all visitors ranked fourth by the AP.

Osborne’s approach in Lincoln was essentially one of continuity—sustaining what Devaney had established. The tradition of Nebraska’s “black shirt” defenses began in 1964 when Devaney first moved to two-platoon football and simply needed to differentiate the defensive and offensive squads. The system quickly evolved into black and grey shirts for the defense, black shirts being awarded on a daily basis to players who had earned them in the previous day’s session. The myth of the “black shirts” only grew under Osborne, who appointed the young Monte Kiffin as defensive coordinator. All-American defensive end John Dutton led Kiffin’s first unit, and while the 1974 black shirts lacked a clear standout they would only give up more than fifteen points on three occasions. On offense Nebraska ran a prototypical power-I, producing multiple 500-yard backs every year. Jeff Kinney ran for 1037 yards in 1971. Tony Davis posted 1008 two years later. With opposing defenses lined up to stop the run, and assisted by talented receivers such as Johnny Rogers, the great ‘Husker teams of the early ‘70s also gained yards through the air. Jerry Tagge exceeded 1300 yards passing each of his three seasons from 1969-71. Dave Humm exceeded 1500 yards every year from 1972-74. Simply put, Nebraska outmatched Wisconsin both sides of the ball.

In contrast, Wisconsin rarely overwhelmed any opponent. Neill Graff’s 1313 yards passing for 11 touchdowns in 1970 constituted the best single-season output by any Badger signal-caller since 1962. Single-digit touchdown totals and completion percentages below fifty were an unwlecome annual tradition. The running game offered some hope, in which Bill Marek’s 1207 yard performance in 1973 made him the third consecutive thousand-yard Badger tailback. Wisconsin’s offensive output gradually improved over Jardine’s first four seasons, but the defense routinely gave up at least three touchdowns. Junior quarterback Greg Bohlig’s 1700 yards passing in 1973 had given hope of better things to come, despite a completion ratio of 45% and a final record of 4-7. With Bohlig and Marek both back, Badger fans expected a relatively productive offense, but few dared to hope that an outmanned defense would hold powerful Nebraska in check.

In contrast, Wisconsin rarely overwhelmed any opponent. Neill Graff’s 1313 yards passing for 11 touchdowns in 1970 constituted the best single-season output by any Badger signal-caller since 1962. Single-digit touchdown totals and completion percentages below fifty were an unwlecome annual tradition. The running game offered some hope, in which Bill Marek’s 1207 yard performance in 1973 made him the third consecutive thousand-yard Badger tailback. Wisconsin’s offensive output gradually improved over Jardine’s first four seasons, but the defense routinely gave up at least three touchdowns. Junior quarterback Greg Bohlig’s 1700 yards passing in 1973 had given hope of better things to come, despite a completion ratio of 45% and a final record of 4-7. With Bohlig and Marek both back, Badger fans expected a relatively productive offense, but few dared to hope that an outmanned defense would hold powerful Nebraska in check.Certainly Nebraska’s sixty-point explosion the previous week gave cause for concern. After the teams exchanged punts early on, Big Red seized the initiative with 6:00 to play in the first quarter. Nebraska took a 7-0 lead on a 22-yard breakaway dash from wingback Don Westbrook. A national television audience watching on ABC likely sensed another runaway victory, but on Nebraska’s next possession David Humm went down with a hip pointer and left the game. That Humm missed the following two Nebraska games but still finished the 1974 season with 1435 yards and12 TDs is sufficient indication of his talent. In his place, career backup Earl Everett went just 3-of-7 with an interception. Everett and Humm’s combined five completions were good for a paltry forty-seven team passing yards. But so long as the untested understudy had only to hand the ball off, Nebraska continued to look marginally the better team.  With 6:14 in the second quarter to play Wisconsin drove half the length of the field before levelling on a nine-yard pass from Bohlig to backup wideout Ron Egloff. After another exchange of punts Nebraska answered with a drive of their own, capped by a six-yard scoring dash from tailback John O’Leary seconds before time expired. As a sophomore the previous year O’Leary had gained 326 yards on 73 carries. Classmate Tony Davis had topped a thousand. Davis and O’Leary would combine for 1025 yards in 1974, before totaling 1118 yards as seniors in 1975. One of the greatest runningback tandems in Nebraska history made a combined 162 yards against Wisconsin, but after O’Leary suffered a concussion early in the second half just four yards shy of a century Davis had to carry the load alone. Missing a thousand-yard passer and a 500-yard back the ‘Husker offense sputtered.

With 6:14 in the second quarter to play Wisconsin drove half the length of the field before levelling on a nine-yard pass from Bohlig to backup wideout Ron Egloff. After another exchange of punts Nebraska answered with a drive of their own, capped by a six-yard scoring dash from tailback John O’Leary seconds before time expired. As a sophomore the previous year O’Leary had gained 326 yards on 73 carries. Classmate Tony Davis had topped a thousand. Davis and O’Leary would combine for 1025 yards in 1974, before totaling 1118 yards as seniors in 1975. One of the greatest runningback tandems in Nebraska history made a combined 162 yards against Wisconsin, but after O’Leary suffered a concussion early in the second half just four yards shy of a century Davis had to carry the load alone. Missing a thousand-yard passer and a 500-yard back the ‘Husker offense sputtered.

Nebraska extended its slender lead to 17-10 five minutes into the second half on a thirty-yard Mike Coyle field goal. The black shirts gave up yardage that threatened the ‘Husker lead only begrudgingly and in tiny increments. Wisconsin rushed for a team total of just 77-yards on a massive forty-four attempts. The 1974 Badgers were far from second-rate on the ground. Marek would finish the year with 1207 yards on 241 carries, including thirty-points and 304-yards against Minnesota that remain first and second on their respective lists of single-game school records. Alongside him Ken Starch added 637 yards on 110 carries while Mike Morgan gained 461 on 85. Against Monte Kiffin’s immovable defensive front, however, the Badgers managed virtually nothing.

Jardine had little option but to shift to the passing game. Bohlig, a talent at least equal to his now-departed opposite number David Humm, answered the call with a 242-yard performance on 14-of-21 passes. He began to find holes in front of the Nebraska secondary, allowing his receivers to maneuver Wisconsin inside the ten-yard line shortly before the third quarter expired. With 14:16 to play in the game the Badger’s struggling ground attack gained a one-yard score through Bill Marek, reducing the deficit to just 17-14.

The teams then exchanged punts for the fifth time before Tony Davis, who finished with seventy-six yards, shouldered most of the load in a drive that carried Big Red inside the Badger ten with barely five minutes remaining. A touchdown would have decided the game, but without two of its leaders the ‘Husker offense reached only the two-yard line in three attempts. Osborne faced a difficult decision. Nebraska gained 258 rushing yards on the day in sixty-two attempts. The odds favored a touchdown on fourth-and two, and with the black shirts still holding Wisconsin’s ground game in check the danger in falling short seemed relatively limited. But Osborn elected to kick, extending the ‘Husker lead to just 20-14.

The teams then exchanged punts for the fifth time before Tony Davis, who finished with seventy-six yards, shouldered most of the load in a drive that carried Big Red inside the Badger ten with barely five minutes remaining. A touchdown would have decided the game, but without two of its leaders the ‘Husker offense reached only the two-yard line in three attempts. Osborne faced a difficult decision. Nebraska gained 258 rushing yards on the day in sixty-two attempts. The odds favored a touchdown on fourth-and two, and with the black shirts still holding Wisconsin’s ground game in check the danger in falling short seemed relatively limited. But Osborn elected to kick, extending the ‘Husker lead to just 20-14.

Wisconsin had less than four minutes remaining to go seventy-one yards after running the ensuing kick back to its own 29-yard line. On first-and-ten the Nebraska defensive front blew past some shoddy blocking and gang tackled the helpless Bohlig for a six-yard loss. Osborne’s gambit seemed momentarily judicious. A 73,000 home crowd, which had been electrified by their team’s goal-line stand, began to sense an anticlimax. Then, on second-and-sixteen, Bohlig again dropped back. His protection held long enough for him to find receiver Jeff Mack on a seam route at the Wisconsin thirty-five. Bohlig hit Mack in a crowd of ‘Husker defenders perfectly in stride, allowing the flanker to break free and sprint the length of the field. The 77-yard touchdown set up a game-winning PAT attempt, which Vince Lamia duly converted to the delight of an already jubilant crowd.

Needing a field length drive with barely three minutes remaining Osborne called a typical off-tackle running play on first down. A resurgent Wisconsin defense swarmed to the ball, forcing Osborne to call a pass play on second down. Nebraska quarterbacks have never been known for making quick yards through the air under any circumstances. Required to do so for an unlikely late comeback Everett threw an interception. A handful of ultra conservative running plays later the clock expired as glory-starved Wisconsin fans stormed the field.

Needing a field length drive with barely three minutes remaining Osborne called a typical off-tackle running play on first down. A resurgent Wisconsin defense swarmed to the ball, forcing Osborne to call a pass play on second down. Nebraska quarterbacks have never been known for making quick yards through the air under any circumstances. Required to do so for an unlikely late comeback Everett threw an interception. A handful of ultra conservative running plays later the clock expired as glory-starved Wisconsin fans stormed the field.

The day was an aberration. Big Red finished the 1974 season 9-3 with a win over Florida in the Sugar Bowl. While the Badgers limped to 7-4 they would not post another winning season until 1981. That one-point win over a depleted Nebraska team easily constituted the greatest win of John Jardine’s disappointing eight-year tenure, and possibly of two barren decades for Wisconsin football. For Big Red, a streak of annual bowl appearances that began in 1969 would stretch to 2004. ‘Husker fans soon forgot their fourth-quarter loss in Madison.

Big Red has not returned to Madison since that day, or played Wisconsin in any other location. On 1 October 2011 Nebraska will play its first Big Ten game at Camp Randall stadium. Over the last decade it has been the Badgers that have enjoyed the high watermark of school history, while Nebraska has languished—relative, of course, to admittedly lofty expectations. Husker fans will hope for a win, however narrow, that might prove not an aberration but the spark for a renewed dynasty.

Whatever happens, Wisconsin will not be held to seventy-seven yards on the ground.

[Sources: USA CFB encyclopedia; ESPN Big Ten encyclopedia; New York Times; Huksers.com,

History of the blackshirts; cfbdatawarehouse.com; huskersmax.com; photos, Madison.com] Illinois coach Ray Eliot Nusspickle had played in Champagne for the legendary Robert Zuppke. The slight but tenacious 190lb lineman had hitchhiked to Illinois from his home in eastern Massachusetts in the fall of 1928. Eliot wore glasses he could barely see without. One assistant coach heavily discouraged him from pursuing football, but Eliot refused to listen and not only made the Illini freshman squad but also became the first bespectacled catcher in Big Ten baseball history.

Illinois coach Ray Eliot Nusspickle had played in Champagne for the legendary Robert Zuppke. The slight but tenacious 190lb lineman had hitchhiked to Illinois from his home in eastern Massachusetts in the fall of 1928. Eliot wore glasses he could barely see without. One assistant coach heavily discouraged him from pursuing football, but Eliot refused to listen and not only made the Illini freshman squad but also became the first bespectacled catcher in Big Ten baseball history.  Eliot coached many fine Illinois teams, but his greatest achievement was undoubtedly leading the surprising 1946 Illini to glory. After an opening win over Pitt the Illini dropped two of the next three games, to Notre Dame and Indiana, scoring only a combined thirteen points in those defeats. Despondent over the lackluster start Eliot tended his resignation, only to have athletics director and basketball coach Donald Mills refuse. Instead Mills appealed to the football players directly, informing them that their poor start had prompted their coach to resign and challenging them to improve their play. The strategy succeeded. Most of the Illini squad consisted of relatively unknown and unheralded commodities. But a few exceptional standouts answered the call and led the team in an unlikely run to Pasadena.

Eliot coached many fine Illinois teams, but his greatest achievement was undoubtedly leading the surprising 1946 Illini to glory. After an opening win over Pitt the Illini dropped two of the next three games, to Notre Dame and Indiana, scoring only a combined thirteen points in those defeats. Despondent over the lackluster start Eliot tended his resignation, only to have athletics director and basketball coach Donald Mills refuse. Instead Mills appealed to the football players directly, informing them that their poor start had prompted their coach to resign and challenging them to improve their play. The strategy succeeded. Most of the Illini squad consisted of relatively unknown and unheralded commodities. But a few exceptional standouts answered the call and led the team in an unlikely run to Pasadena.

one of the most dangerous service jobs as a B-42 top-gunner. In early 1944 Dufelmeier’s plane was shot down over France. He spent eleven months as a POW inside Germany, losing 35lb before liberation. Simply glad to be alive, Dufelmeier relished his return to football in 1946.

one of the most dangerous service jobs as a B-42 top-gunner. In early 1944 Dufelmeier’s plane was shot down over France. He spent eleven months as a POW inside Germany, losing 35lb before liberation. Simply glad to be alive, Dufelmeier relished his return to football in 1946.

The Illini prevailed in an outright romp, 45-14. Eliot’s squad held the Bruins to just twelve first downs and forced six demoralizing turnovers. Most incredibly, the Illini held a team that had run roughshod over the west coast to a paltry sixty-two rushing yards. Only 176 passing yards on 29 attempts from Case afforded any offensive success. Despite their lesser physical stature Illinois racked up 320 team rushing yards, including 100-yard performances from both Young and Dufelmeier.

The Illini prevailed in an outright romp, 45-14. Eliot’s squad held the Bruins to just twelve first downs and forced six demoralizing turnovers. Most incredibly, the Illini held a team that had run roughshod over the west coast to a paltry sixty-two rushing yards. Only 176 passing yards on 29 attempts from Case afforded any offensive success. Despite their lesser physical stature Illinois racked up 320 team rushing yards, including 100-yard performances from both Young and Dufelmeier.

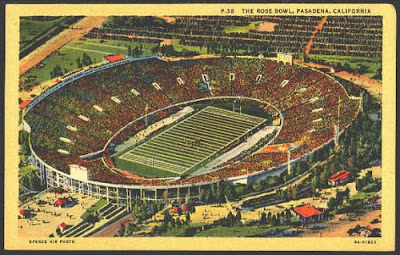

Only once during the three decades after 1916 did a member of the Big Ten Conference repeat Michigan’s appearance in the experimental 1902 scrimmage. John Wilce’s 7-0 Buckeyes traveled to face California on New Year’s Day 1921, and were solidly beaten 28-0. Faculty representatives on the Ohio State University athletics board subsequently decided that the academic disruption the trip involved for participating students constituted an undue burden. The university decided to decline any future invitation to post-season games. Faculty members at the other Big Ten member schools followed suit, establishing a conference-wide rule against post-season play which lasted a quarter century. Ohio state's decision was hardly unusual. Despite defeating Stanford 27-10 in the 1925 Rose Bowl, Notre Dame University decided against future post-season play and did not accept another bowl invitation until 1969. Navy had made a similar decision the previous year after playing Washington to a 14-14 tie. The Midshipmen made no further bowl appearance until 1955.

Only once during the three decades after 1916 did a member of the Big Ten Conference repeat Michigan’s appearance in the experimental 1902 scrimmage. John Wilce’s 7-0 Buckeyes traveled to face California on New Year’s Day 1921, and were solidly beaten 28-0. Faculty representatives on the Ohio State University athletics board subsequently decided that the academic disruption the trip involved for participating students constituted an undue burden. The university decided to decline any future invitation to post-season games. Faculty members at the other Big Ten member schools followed suit, establishing a conference-wide rule against post-season play which lasted a quarter century. Ohio state's decision was hardly unusual. Despite defeating Stanford 27-10 in the 1925 Rose Bowl, Notre Dame University decided against future post-season play and did not accept another bowl invitation until 1969. Navy had made a similar decision the previous year after playing Washington to a 14-14 tie. The Midshipmen made no further bowl appearance until 1955.

The decision to approach a southern school in 1925 proved a turning point for the Rose Bowl, and the entire history of post-season collegiate football. The Crimson Tide edged Washington in a 20-19 thriller, earning new respect for southern football. Alabama football gained popularity within the south and the praise of sports journalists nationally. Dixie remained an under-populated social and economic backwater. The south rarely made national headlines for good reasons. University of Alabama administrators viewed the trip as more than worthwhile. The following year Wallace Wade's Crimson Tide became the first repeat visitor to the Rose Bowl, playing Stanford to a tough 7-7 tie. Alabama made five further appearances in Pasadena over the next two decades, building much of the university’s early legacy of football greatness on the edifice of a 4-1-1 Rose Bowl record. Other schools saw an opportunity to garner some of the interest and heightened prestige that the Big Ten, Notre Dame, and military academies had to spare. Between 1928 and 1945 Duke, Georgia Tech, Georgia, Tulane, Southern Methodist, and Tennessee [twice] each made the trip to Pasadena, often providing thrilling games and drawing sell-out crowds. Rising eastern independent Pittsburgh boosted its growing reputation with four appearances.

By the mid-thirties, just a decade after Alabama’s first visit, the Rose Bowl had established itself as such a popular, thrilling, prestigious, and lucrative annual sporting fixture that entrepreneurial city fathers in several southern towns decided to follow suit. Since 1907 the Havana Athletics Club had intermittently hosted post-season visits from southern schools. Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario held a few similar games against mid-Atlantic region guests. Several other cities held one-time games pitting their hometown team against a visitor, such as the 1921 “Fort Worth classic”. But the Rose Bowl had offered the only annual post-season clash between a regional champion and the best willing and available guest. After the Sugar, Orange, and Cotton Bowls entered the picture in 1935 and 1936, New Year’s Day emerged as one of the great national spectacles on the American sporting landscape. Fans and journalists flocked to games which allowed participating universities to crown successful seasons by showcasing their varsity squads in the national limelight. A share of the gate receipts provided a welcome bonus.  Despite the obvious success of their annual fixture, Tournament of Roses organizers and Pacific Coast Conference members continued to fret over the annual headaches of selecting a guest. Southern schools provided interesting games, but the east and mid-west remained the demographic and economic heartland of the nation. After 1935 the Rose Bowl faced the added threat that southern teams would in future prefer bids to play closer to home in Dallas, New Orleans, or Miami. From the mid-thirties onwards the PCC made repeated overtures to the Big Ten [then still more commonly referred to by its original moniker dating to the league’s inception in 1896, the Western Conference] to establish a formal relationship with the Rose Bowl. Not until 1946 did those efforts bear any fruit.

Despite the obvious success of their annual fixture, Tournament of Roses organizers and Pacific Coast Conference members continued to fret over the annual headaches of selecting a guest. Southern schools provided interesting games, but the east and mid-west remained the demographic and economic heartland of the nation. After 1935 the Rose Bowl faced the added threat that southern teams would in future prefer bids to play closer to home in Dallas, New Orleans, or Miami. From the mid-thirties onwards the PCC made repeated overtures to the Big Ten [then still more commonly referred to by its original moniker dating to the league’s inception in 1896, the Western Conference] to establish a formal relationship with the Rose Bowl. Not until 1946 did those efforts bear any fruit.

By the end of WWII post-season bowls had become sufficiently established that athletics personnel within numerous Western Conference member schools began to consider an end to the prohibition on post-season play. Needing little encouragement, representatives of the ten PCC schools voted unanimously to extend a formal invitation early in the 1946 season for the Big Nine [as the conference was briefly known following Chicago’s withdrawal that year] to enter a long-term agreement regarding Rose Bowl participation. Ohio State’s board of regents led the way in overturning the post-season ban their school had originally established by approving the potential agreement on September 25th. OSU president Wilbur St. John told reporters:

“I have always been in favor of having the two conference winners meet, and I feel confident in saying that all Big Nine coaches and athletics directors share my opinion. However, it is a matter for the faculty to decide.”

Three weeks later conference commissioner Kenneth Wilson convened an informal meeting in Chicago at which members voted five to four in favor of pursuing the PCC proposal further. Minnesota, Illinois, Northwestern, and Purdue cast the dissenting votes, with Illinois faculty representatives providing the most outspoken opposition to the academic disruptions bowl trips involved for student-athletes. Due to such concerns the Chicago meetings drafted numerous provisions for a counter proposal qualifying the terms on which the Big Nine would consider participation. The narrow majority tentatively approved a five-year Rose Bowl agreement but reserved the right for the Big Nine champion to decline a bid and send another conference member instead. The conference further stated that the same representative would not appear more than once over a three-year period, and also requested the privilege of nominating a non-Big Nine independent [newspapers presumed Notre Dame] to appear in case no conference member wished to accept.

Collectively the reservations amounted to a complete assumption for five-years of the Rose Bowl committee’s invitational prerogatives. But the PCC remained enthusiastic. Stanford athletics director Alfred Masters told reporters:

“It would be a great thing if it happened. A permanent fixture of this kind would assure us a high-class opponent every year.”

University of California athletics director Clinton Evans was even more explicit regarding what the PCC stood to gain. He told reporters:

"We would welcome an opportunity to have the Western Conference champion meet the Pacific Coast champion every year in the Rose Bowl. It would eliminate the necessity of sending out invitations in December. The Big Nine plays an outstanding type of football every year."

In other words, Evans and his colleagues worried about the same question that still haunts bowl organizers in 2011 — not how to secure a chance at lining up the best possible matchup, but how to eliminate the chance of ending up with an unattractive fixture.

The timing of the agreement Schmidt carried back to California for final approval by PCC members was ironic for two reasons. Firstly, Illinois [whose faculty had most virulently opposed the plan] led the Big Nine standings. Two days after the Chicago meeting the Illini defeated Ohio State 16-7. Only in-state rival Northwestern stood between them and a first conference crown since 1928. A win would give Illinois first right of refusal on a bowl bid it had vocally opposed the conference receiving. Secondly, while the pact was designed to preclude the risk of the Pacific Coast champion hosting a relatively unattractive opponent, by far the most prestigious guest available in 1946 did not belong to the Big Nine. Earl Blaik’s great wartime Army teams, led by Heisman winners “Doc” Blanchard and Glenn Davis, had not lost a game since falling to Navy in 1943. The Cadets crushed Penn 34-7 in Philadelphia on November 16th and had only the Midshipmen to beat for a second consecutive unbeaten season. Unofficially, West Point did not accept bowl bids, but Superintendent Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor explicitly left the door open. The same day that Big Nine officials met in Chicago, Maxwell told journalists.

The timing of the agreement Schmidt carried back to California for final approval by PCC members was ironic for two reasons. Firstly, Illinois [whose faculty had most virulently opposed the plan] led the Big Nine standings. Two days after the Chicago meeting the Illini defeated Ohio State 16-7. Only in-state rival Northwestern stood between them and a first conference crown since 1928. A win would give Illinois first right of refusal on a bowl bid it had vocally opposed the conference receiving. Secondly, while the pact was designed to preclude the risk of the Pacific Coast champion hosting a relatively unattractive opponent, by far the most prestigious guest available in 1946 did not belong to the Big Nine. Earl Blaik’s great wartime Army teams, led by Heisman winners “Doc” Blanchard and Glenn Davis, had not lost a game since falling to Navy in 1943. The Cadets crushed Penn 34-7 in Philadelphia on November 16th and had only the Midshipmen to beat for a second consecutive unbeaten season. Unofficially, West Point did not accept bowl bids, but Superintendent Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor explicitly left the door open. The same day that Big Nine officials met in Chicago, Maxwell told journalists. On November 19th the Presidents and athletics directors of all ten PCC members met in Berkeley. Schmidt and Kenneth Wilson were present to sign the agreement if officially approved. But by the time of the meeting every major west coast newspaper had called for the Rose Bowl to invite Army. Administrators at USC and UCLA both publically favored that option. A closed-door meeting approved the five-year deal but initially left the door open to defer the start date to the 1947 season. The value of Army as a bowl participant could not be doubted when on November 20th, immediately after receiving news that the PCC had approved the pact, Sugar bowl president Sam Corenswet issued a formal invitation to the Cadets.

On November 19th the Presidents and athletics directors of all ten PCC members met in Berkeley. Schmidt and Kenneth Wilson were present to sign the agreement if officially approved. But by the time of the meeting every major west coast newspaper had called for the Rose Bowl to invite Army. Administrators at USC and UCLA both publically favored that option. A closed-door meeting approved the five-year deal but initially left the door open to defer the start date to the 1947 season. The value of Army as a bowl participant could not be doubted when on November 20th, immediately after receiving news that the PCC had approved the pact, Sugar bowl president Sam Corenswet issued a formal invitation to the Cadets.  "We did everything in our power to make it possible for the U.S. Military Academy team to play in the Rose Bowl game, recognizing from the beginning the strong public interest in seeing the unbeaten Army team play in this traditional New Year’s classic. Representatives of the Big Nine, however, stated that if the postponement occurred it would be necessary for them to return to their conference for further action, with considerable doubt as to the outcome. I regret very much that it was made impossible for Army to be the eastern representative in the 1947 Rose Bowl game, although I am fully appreciative of the advantages of the agreement now completed with the Western Conference.”

"We did everything in our power to make it possible for the U.S. Military Academy team to play in the Rose Bowl game, recognizing from the beginning the strong public interest in seeing the unbeaten Army team play in this traditional New Year’s classic. Representatives of the Big Nine, however, stated that if the postponement occurred it would be necessary for them to return to their conference for further action, with considerable doubt as to the outcome. I regret very much that it was made impossible for Army to be the eastern representative in the 1947 Rose Bowl game, although I am fully appreciative of the advantages of the agreement now completed with the Western Conference.” Jim Delany: persona non grata among college football's have-nots

Jim Delany: persona non grata among college football's have-nots

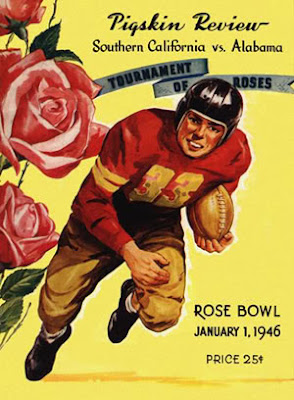

During the late afternoon of New Years’ Day 1946, with the clock running out on the thirty-second Rose Bowl, Southern Cal reserve tackle Myron Doornbos penetrated the Alabama line and blocked a Gordon Pettus punt. Trojan end Chuck Clark scooped up the loose ball on the Bama five-yard line and ran it home for a score. The touchdown, SC’s second of the final period, put a veneer of respectability on what had been a lopsided rout. The Crimson Tide ran out 34-14 winner, taking the University of Alabama’s all-time record in the Pasadena classic to 4-1-1. Since its first appearance at the Tournament of Roses in 1927 Alabama had been the most frequent and successful guest. The southern powerhouse would also be the last non-Big Ten visitor for more than half a century.

During the late afternoon of New Years’ Day 1946, with the clock running out on the thirty-second Rose Bowl, Southern Cal reserve tackle Myron Doornbos penetrated the Alabama line and blocked a Gordon Pettus punt. Trojan end Chuck Clark scooped up the loose ball on the Bama five-yard line and ran it home for a score. The touchdown, SC’s second of the final period, put a veneer of respectability on what had been a lopsided rout. The Crimson Tide ran out 34-14 winner, taking the University of Alabama’s all-time record in the Pasadena classic to 4-1-1. Since its first appearance at the Tournament of Roses in 1927 Alabama had been the most frequent and successful guest. The southern powerhouse would also be the last non-Big Ten visitor for more than half a century.

Frank Thomas with Harry Gilmer,Thomas Whitely, Gordon Pettus and Henry Self

That kind of physicality gave Bama a decided advantage over Newell "Jeff" Cravath’s 7-3 Trojan squad, which actually outweighed the Tide by an average of eight pounds a man. 320-pound tackle Jay Perrin — a giant in that era — led a strong line that allowed star halfback Ted Tannehill to run roughshod over most of the Pacific coast’s other squads. Though odds-makers had the second-ranked Tide as a touchdown favorite, no Southern Cal squad had failed to win the Rose Bowl classic in eight appearances. Most of the 93,000-strong partisan crowd hoped and expected that the Trojans would find a way to prevail.

It took only two plays for the those hopes to being unraveling. On second down, Tannehill fumbled in the Trojan backfield. Hefty Alabama right guard Jack Green to recovered on the fifteen. Four plays later quarterback Henry Self reached the endzone on a two-yard sneak. The two sides exchanged punts through the remainder of the first period before Gilmer took control. On the first Bama possession of the second quarter the Tide marched sixty-eight yards in eleven plays. Gilmer called the plays, distributed the ball, and went across himself for the drive-capping play from the SC five. Behind the blocking of Mancha and Green — the standout performers in an excellent frontline — Bama’s backs enjoyed gaping holes and frequently reached the Trojan secondary untouched.

On the final Tide possession of the first half Frank Thomas’s men showed their squad depth as the second string offense romped to a sixty-four yard scoring drive on just four plays. Gordon Pettus, Gilmer’s understudy at halfback, broke free for a fifty-one yard run before Trojan backs finally dragged him down inside the five-yard line. Tew finished the process with a two-yard plunge at right end. Southern Cal’s struggles only mounted after the break as Alabama continued to hog the ball, putting together another scoring drive on seven plays on its first possession. A big kickoff return set the Tide up inside SC territory. Tew, Gilmer, and fullback Norwood Hodges then alternated runs to cover thirty-nine yards before Hodges finished with another short dive to the endzone. Gilmer completed a masterful performance early in the fourth quarter with a twenty-five yard touchdown pass to Self, putting the Tide ahead 34-0.

Alabama racked up 292 rushing yards and eighteen first downs, allowing Gilmer to pick his moments in the passing game. Four completions in twelve attempts added an unspectacular but useful fifty-nine yards and a score with one interception. Perhaps more impressively, Alabama’s frontline dominance was equally marked on defense. The Trojans managed just six net yards rushing, three first downs [all in the fourth quarter], and only thirty-five yards passing. Tide defenders also added to the home team’s woes with two interceptions. Southern Cal’s stars simply never found their rhythm. It seemed they couldn’t buy a break. On the kickoff following Gilmer’s final score, with most of Alabama’s third string unit in the game, Tannehill ran the ball back ninety yards only to see the play called back on an offside penalty.

Ted Tannehill going nowhere

The Trojans finally managed a little offensive output before a deep punt backed Alabama up to their own twenty-five. SC’s line then held the visitors in check, forcing Pettus to fumble. Big Jay Perrin recovered, setting up Trojan halfback Verl Lilywhite to roll out and hit left end Harry Aldeman for a touchdown pass on the ensuing play. That strike accounted for almost all of Southern Cal’s positive offensive yards in the final box score. Following the kick-off SC again prevented the Alabama reserves from making a first down, forcing the punt which Doornbos blocked on the game’s final scoring play. Two late scores were perhaps a just reward for the Trojans, who continued to put forth full effort during an utter rout at the hands of an obviously superior opponent. But the final score-line did no justice to Alabama’s dominating performance.

Coach Thomas’s Crimson Tide silenced the California crowd. Earl Blaik’s unbeaten Army squad, led by Glenn Davis and Doc Blanchard, had been voted national champion by the Associated Press. West Point did not accept bowl invitations in those days [and would not do so until 1984], denying Alabama the chance to test themselves against the very best. But in every sense they could have proved, the Crimson Tide were champions.

Years later Gilmer would remember of the game:

“We beat Southern Cal 34-14, and it wasn’t that close. After that the Rose Bowl shut Alabama and the other southern schools out.”

From New Years’ Day 1947 until the Miami Hurricanes faced Nebraska in the 2001 season Bowl Championship Series title game, the Rose Bowl would only host visitors from the Big Ten. To this day University of Alabama lettermen, alumni, and fans will tell anyone who cares to listen that Tournament of Roses organizers took that decision because they were sick of the Crimson Tide embarrassing the west coast champion. And there may be some truth to their argument.

[Sources: New York Times; McNair, What it Means to be Crimson Tide].

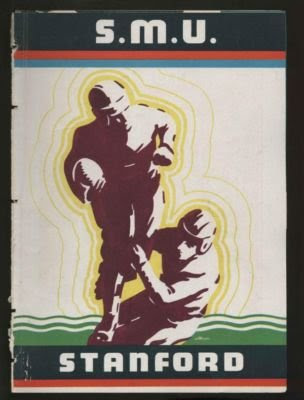

On New Years’ Day 1936 the SMU Mustangs represented the Southwest Conference 2,000 miles from home in the Rose Bowl — the first Texas school to do so, and the last for seventy years. To their opponent, Stanford, the Pasadena showcase was nothing new. The appearance was the sixth in school history and third consecutive. Having lost the previous two Rose Bowl Games to Columbia in 1934 and then an Alabama squad in 1935 that featured a young end named Paul Bryant, the Indians were in no mood to let SMU take the laurels.

On New Years’ Day 1936 the SMU Mustangs represented the Southwest Conference 2,000 miles from home in the Rose Bowl — the first Texas school to do so, and the last for seventy years. To their opponent, Stanford, the Pasadena showcase was nothing new. The appearance was the sixth in school history and third consecutive. Having lost the previous two Rose Bowl Games to Columbia in 1934 and then an Alabama squad in 1935 that featured a young end named Paul Bryant, the Indians were in no mood to let SMU take the laurels.

Facing Stanford that clear, sunny January 1st was a team that provided both a mirror image and a stark juxtaposition. The top-ranked, unbeaten Ponies were also at the height of their program’s historical powers. And SMU also featured two all-America selections — left halfback Bobby Wilson and powerful left guard J. C. Wetsel. Like Stanford, SMU had only recently parted ways with a legendary coach. After three conference championships in thirteen seasons and an 84-44-23 record Ray Morrison had returned home to coach his alma mater, Vanderbilt, the preceding year. Morrison’s successor, Madison “Matty” Bell would achieve a 79-40-8 mark through twelve seasons, including a perfect 12-0 regular season his first year. Bell, a Fort Worth native, had played for tiny Centre College in Kentucky, and had coached at TCU and then Texas A&M prior to taking the SMU job. Bell led his team past his former employer TCU and its great star Slingin’ Sammy Baugh in a 20-14 thriller to clinch the Rose Bowl berth. Both TCU and SMU employed offensive styles that the New York Times called:

“…the wide open style of play that has been increasingly adopted in all sections except the west coast.”

True to form the Rose Bowl unfolded as a battle of old versus new school, each team continuing the approach that had carried them so far. Stanford attempted only five forward passes, completing just 2-for-43. Two were intercepted. In contrast the Indians ground out a relatively productive 113 yards on the ground, and elected to punt fifteen times. As was not uncommon in football through the 1930s, many of Stanford’s punts were surprise “quick kicks” on first down designed to pin the opponent deep when no return man could run the ball back. With senior quarterback and Pasadena native Bill Paulman punting for a forty-yard average and the larger Stanford line successfully hurrying the SMU pass-attack, the quick kick strategy proved remarkably effective. Using field position and conservative play Stanford outlast SMU for a final score of 7-0. And that despite being outgained by a margin of seventy-one passing yards and nine Pony first downs to just six for the Indians.

A surprise kick actually set up the game’s only score late in the first quarter. At midfield on first down Paulman pinned SMU on their five-yard line. The Ponies could not escape and kicked back. Their punting would be second-rate all day. Quarterback John Sprague and halfback John Finley shared eleven punts for just a thirty-four yard average. When Finley kicked the ball out of his endzone in the first quarter he was horrified to see halfback James Coffis return it fifteen precious yards. Working from the Pony forty-two Stanford took advantage with an uncharacteristic play when Grayson threw a twenty-three yard completion to Coffis. After two rushes for no gain Grayson burst around right end for seventeen yards. On the next play a reverse to left halfback Bob “Bones” Hamilton carried Stanford to the one-yard line, from whence Paulman stepped home running free as a fake hand-off to Hamilton motioned the SMU line to the wrong direction.

Despite having gained a touchdown with relatively creative play Thornhill decided to withdraw into more cautious tactics for the remaining three quarter, seeking to preserve the Indians’ one-score lead. SMU passed the ball thirty times, an amazing number for the era. Unfortunately the Stanford line successfully penetrated the Pony backfield with enough regularity to disrupt the SMU air-attack. The Ponies never managed to complete passes with sufficient consistency to throw keep drives moving. Occasional short gains were peppered with enough incompletions that while SMU’s tactics impressed the predominantly West Coast crowd, they availed little. Finley, Wilson, and Sprague combined for only 11-of-30 passing. Worst of all, they were picked off a crippling six times — usually at decisive moments which allowed Stanford to “bend but not break” on defense before the phrase had been coined.

Stanford defenders breaking up SMU's usually reliable passing attack

Stanford defenders breaking up SMU's usually reliable passing attack

The great 1935 SMU Mustangs

Bell’s team, the rapturously received SMU marching band, and the quaintly dressed Texas boosters all returned the 2,000 miles home with nothing. The one fanatic who hitch-hiked the entire way must have felt particularly disappointed. Doubtless, however, he never regretted making the trip. Not only has SMU never returned to Pasadena, but until the BCS era they remained the only Texas school to have made the trip. Not until Oklahoma crushed Washington State 34-14 on New Years’ Day 2003 did another former Southwest Conference member play in the “Granddaddy” [OU was a charter member of the SWC in 1915 but remained only until 1919]. Two years later the University of Texas played a thriller against fellow historical heavyweight Michigan, running out a one-point winner in a 38-37 final. Texas returned the following year to upset USC behind the incredible Vince Young, coming back late to win 41-38.

This year, on January 1st 2011 the TCU Horned Frogs became only the third Texas school to play in Pasadena, and the only one besides UT to be crowned champion. Senior quarterback Andy Dalton succeeded where even Slingin’ Sammy had failed in 1935, leading the Frogs to college football’s most prestigious bowl game. He also succeeded where Bob Wilson had failed, leading his team past a bulkier Wisconsin squad to a thrilling 21-19 win. Like SMU, the Horned Frogs will almost certainly never be asked to return. But like the Dallas man who loved his 1935 Ponies enough to thumb his way to California and back, no one in Fort Worth cares. The little guys from the old Southwest Conference had their day in the sun.

[Sources: New York Times; Fort Worth Star-Telegram]

LaVell Edwards: legend

None of the Utah Utes who surged off their team's bench to celebrate on the Cougars' home field could even remember the day exactly two decades earlier that their school had last triumphed in Provo. Who could blame them for attempting in their momentary euphoria to tear down the BYU goal-posts? As Ute receiver Bryan Rowley later told a reporter:

"We were just excited. That's over twenty years of frustration... If they hadn't won in twenty years, they would feel the same way."

In fact, BYU players, fans, and coaches did not see things so philosophically. Cougar players rushed to the endzone and attempted to initiate a mass brawl rather than watch their hated foe rip down their goal-posts. A few handbags, insults, pushes, and shoves later, stadium security and coaches separated the groups and the incident was over. BYU's hurt pride, however, was less quick to subside. In an unguarded comment after the game, nose guard Lenny Gomes allowed the disdainful arrogance which had come to characterize Cougar attitudes towards their in-state rival bubble to the surface:

"Typical Utah bulls. All those Utes think that's all there is to life. But when I'm making $50,000-$60,000 a year, they'll be pumping my gas. They're low-class losers."

What more there might be to life than an impressive annual salary Gomes failed to discuss. LaVell Edwards was more diplomatic, only saying that he had never seen anything like a visiting team attempting to tear down the home goal-posts and refusing further comment on the subject.

It is natural for football personnel and fans to see their rivals' actions in the worst possible light. That is exactly what makes rivalries such an integral, wonderful part of the fabric of college football. But perhaps BYU people should have taken a step back and thanked their good fortune that after fifty years of futility in the series their school had so emphatically seized the upper hand that Utah players would react to beating them in such a dramatic fashion. Doubtless the Ute reaction followed no premeditated plan to offer specific offense. The elation surrounding the moment of victory had been as much a factor of the game's final few possessions as the context of the preceding two decades. Typical of the fast paced aerial explosions that defined the Edwards era, the two teams had thrown the ball around as though passing was about to go on ration. BYU quarterback John Walsh compiled 423 yards on 35 completions in a stereotypically massive 57 attempts with a touchdown. His counterpart Mike McCoy answered yard for yard, going 30-of-49 for 423 yards and 3 TDS. The difference makers on the day turned out to be Utah's 167 team rushing yards on 39 carries [as opposed to just 78 on 20 for BYU], and Walsh's careless, season-high five interceptions. BYU picked off McCoy only twice.

Doubtless the Ute reaction followed no premeditated plan to offer specific offense. The elation surrounding the moment of victory had been as much a factor of the game's final few possessions as the context of the preceding two decades. Typical of the fast paced aerial explosions that defined the Edwards era, the two teams had thrown the ball around as though passing was about to go on ration. BYU quarterback John Walsh compiled 423 yards on 35 completions in a stereotypically massive 57 attempts with a touchdown. His counterpart Mike McCoy answered yard for yard, going 30-of-49 for 423 yards and 3 TDS. The difference makers on the day turned out to be Utah's 167 team rushing yards on 39 carries [as opposed to just 78 on 20 for BYU], and Walsh's careless, season-high five interceptions. BYU picked off McCoy only twice.

Despite jumping out to a 14-3 fist quarter lead behind drives of 68 yards on six plays and 80 yards on nine, Utah had allowed the Cougars back into the game. Although BYU briefly levelled the game late in the third quarter the Utes responded immediately and appeared to be back in the driving seat, as they had most of the day. After a touchback on BYU's kick Utah started on their own twenty and gained nothing on two plays. Sensing the shift in momentum a three-and-out would provide following their offense's game-tying score, the Cougar safeties moved up and showed blitz. McCoy anticipated the pressure and called an audible for receiver Curtis Marsh to come over the middle. The Ute quarterback called for the snap from the shotgun formation and quickly dumped it to an open Marsh behind the BYU pass-rush. He then ran 80 yards to the endzone and shed much of the frustration of his injury-plagued year in one glorious play.  On the back of such a stunning score Utah players were riding high. As a result, BYU's successive fourth quarter come-back drives must have created intense frustration on the Utah sideline. The long awaited road win that seemed so tantalizingly also refused to come completely within reach. The bad news began with a missed PAT following Marsh's TD by Utah kicker Chris Yergensen. The Ute specialist had already missed two mid-range field goals. Seven wasted points seemed so precious when BYU responded immediately with a nine play drive provided an immediate response and despite all of Walsh's interceptions gave BYU a one-point lead. But the Utes wouldn't give up either and retook the lead with less than five minutes remaining on an impressively conducted eighty-yard drive in fourteen plays that included a clutch 17-yard McCoy strike on third and ten to bring the Utes inside the Cougar redzone. A touchdown and successful two-point conversion restored a seven point lead, but again BYU answered. Walsh finished a scoring drive with a one-yard sneak after moving his offense 64-yards in 4 previous plays that included completions of 30 and 19 yards.

On the back of such a stunning score Utah players were riding high. As a result, BYU's successive fourth quarter come-back drives must have created intense frustration on the Utah sideline. The long awaited road win that seemed so tantalizingly also refused to come completely within reach. The bad news began with a missed PAT following Marsh's TD by Utah kicker Chris Yergensen. The Ute specialist had already missed two mid-range field goals. Seven wasted points seemed so precious when BYU responded immediately with a nine play drive provided an immediate response and despite all of Walsh's interceptions gave BYU a one-point lead. But the Utes wouldn't give up either and retook the lead with less than five minutes remaining on an impressively conducted eighty-yard drive in fourteen plays that included a clutch 17-yard McCoy strike on third and ten to bring the Utes inside the Cougar redzone. A touchdown and successful two-point conversion restored a seven point lead, but again BYU answered. Walsh finished a scoring drive with a one-yard sneak after moving his offense 64-yards in 4 previous plays that included completions of 30 and 19 yards.

With both defenses apparently AWOL, the desperate struggle had reached the point at which victory would likely go to the team that possessed the ball last. With barely over a minute remaining that was Utah, but after the BYU kicking coverage team pinned the Utes well inside their own twenty a score seemed unlikely. McCoy and the Ute offense ground out 47 yards on ten plays before sputtering out at the BYU 45-yard line with just 00:25 on the game clock. Up against BYU's ever-dangerous passing offense, turning the ball over on downs at the half way line with twenty ticks still to play would have been risky. Handing the opportunity for redemption to Yergensen seemed an unlikely bet for Ute coach Ron McBride, but there was no alternative.

Clearly the football gods had decided it was time for momentum in the Holy War to shift back from Church to State. The previously luckless kicker somehow curved a perfect effort through the uprights from fifty yards, going in an instant from Utah football infamy to glory. The Utah bench exploded and was still in the throes of jubilation when the clock expired.

Perhaps Utah fan R. J. Aiello summed up the context most astutely:

"It's not just between BYU and Utah. Its a lifestyle conflict."

That's exactly what it is. The Holy War is a unique and precious rivalry in college football because there is no other dynamic that matches a flagship religious school with a public institution whose fans are, in many cases, so very different. BYU people are typically modest in lifestyle but with a barely concealed arrogance and disdain towards their wayward, worldly Ute kin. Utah fans, on the other hand, respond with the brash, unapologetic immodesty that smacks of the rebellious teen acting up in the sight of a disapproving parent. This dynamic doubtless fueled the ironic chants of "Repent! Repent!" which rang out from a tiny corner of the Utah faithful that night in Cougar Stadium.

Utah and BYU fans do not like one another. Both believe the other party to be arrogant and misguided. Both harbor an unbridled sense of superiority. Feelings run high and parties are easily offended. That is doubtless why when Utah received an invitation from the big leagues this summer, BYU athletics director Tom Holmoe and President Cecil Samuelson responded with a plan to lead Cougar football out of Mountain West obscurity and into [potentially equally obscure] independence.

Utah and BYU fans do not like one another. Both believe the other party to be arrogant and misguided. Both harbor an unbridled sense of superiority. Feelings run high and parties are easily offended. That is doubtless why when Utah received an invitation from the big leagues this summer, BYU athletics director Tom Holmoe and President Cecil Samuelson responded with a plan to lead Cougar football out of Mountain West obscurity and into [potentially equally obscure] independence.

At the time of writing, BYU's quest for football independence in order to allow a renewed relationship with ESPN has five more days to play out. According to the most recent rumors this process could damage or destroy no less than three conferences [one of which BYU was the leading party in founding] without actually improving the Cougars' position in the CFB landscape. Whatever happens, one thing is certain: BYU people hate Utah people so much that they don't respond well to seeing them get a bid to the rich, pretty girl sorority while they are left to hang out with the chubbies.

University of Utah administrators, on the other hand, are now so high on their new found status as members of the sport's bourgeoisie that they are openly talking about not playing BYU every year or at least moving the game to an earlier date. Some rumors even indicated that Utah people have flirted with suggesting a two-for-one structure, which BYU people would surely sacrifice their children before accepting.

Such talk on both sides is silly. Schools need an annual rival, preferably one played each year as a final date towards which all preceding games build. If Utah thinks they can live without that, they should ask Nebraska how well Colorado does as a replacement for an annual November date with a hated conference foe. And frankly, college football as a whole needs a rivalry filled with so much hate that things get more than a little religious and end in the occasional brawl.

Good, clean fun!

[Sources: Salt Lake Tribune; CFBdatawarehouse.com]