A thrilling game finished in a 19-18 BC win after the Eagles took an intentional safety on an end-zone punt in the dying minutes, leaving Georgetown insufficient time to reach field goal range. An exciting game shifted in momentum several times. The Hoyas jumped out to a 10-0 first quarter lead before BC posted sixteen unanswered in reply. Huge runs and an unusually large number of downfield passing plays allowed a Boston College backfield that was gaining national recognition to shine.

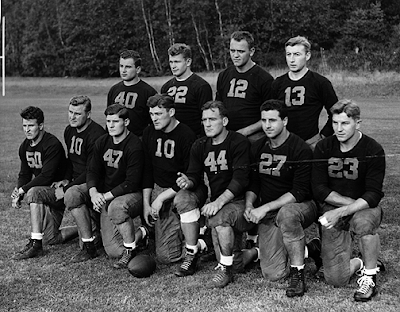

Eagles greats quarterback “Chuckin’ Charlie O’Rourke, and fullback (later head coach) Mike Holovak led the lineup, but many felt the Eagles’ best player in Leahy’s squads

was a little 5’7” halfback named Lou Montgomery. With time expiring in the second quarter and BC on the Hoyas' twenty-two Leahy outmaneuvered Haggerty and seized momentum with a trick play. O’Rourke threw a backfield lateral to Montgomery, as BC often did to get their runner into open space, but the halfback rolled out to his right, drawing defenders up, and threw a touchdown pass to tight end Woronicz. Despite a fourth quarter Georgetown surge, that touchown effectively gave the Eagles control of the game's momentum.

was a little 5’7” halfback named Lou Montgomery. With time expiring in the second quarter and BC on the Hoyas' twenty-two Leahy outmaneuvered Haggerty and seized momentum with a trick play. O’Rourke threw a backfield lateral to Montgomery, as BC often did to get their runner into open space, but the halfback rolled out to his right, drawing defenders up, and threw a touchdown pass to tight end Woronicz. Despite a fourth quarter Georgetown surge, that touchown effectively gave the Eagles control of the game's momentum.BC’s official roster did not list “Lightnin’ Lou” as a starter, despite his significant playing time in three varsity seasons from 1938 to 1940. The 160lb slashing back was a famed open field runner and drew much attention from scouts of future opponents. He suffered no serious injury problems, always had the right attitude, and never faced a defense that bested him. Despite all that, Montgomery spent several crucial games watching from the sidelines and did not participate in the 1940 Cotton Bowl or 1941 Sugar Bowl. Montgomery lost so much playing time and was never allowed to fulfill his true potential as a college athlete because he was black.

Boston College football stood at a cross roads in the late 1930s. BC had played varsity football since 1893 but had never attained national significance. Before WWI the Ivy League dominated East Coast football and Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame stood without rival or peer above all Catholic colleges. But as the 1920s gave way to the 30s Ivy League schools began to deemphasize

football, fearing the sport was eclipsing academic priorities, and Notre Dame suffered declining fortunes during the post-Rockne era. After decades of struggling to earn respect as an Eastern Independent, athletic administrators at BC saw an opportunity to increase the prestige of their institution by succeeding in football.

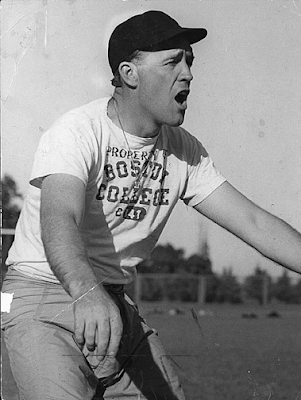

football, fearing the sport was eclipsing academic priorities, and Notre Dame suffered declining fortunes during the post-Rockne era. After decades of struggling to earn respect as an Eastern Independent, athletic administrators at BC saw an opportunity to increase the prestige of their institution by succeeding in football.College President Father William Murphy and graduate director of athletics John Curly hitched the program's fortunes to the young Frank Leahy in 1938. Leahy felt that BC needed to improve the caliber of their opponents if they were to command national attention. Murphy and Curly saw that step as vital to increasing lucrative ticket revenues. Games against St. Anselm, Providence, McDaniel College (MD), New Hampshire and the like carried little weight with wire service pollsters. For BC to gain the attention of bowl selection committees they needed to play inter-sectional games, and especially against teams from areas that hosted bowls. Since trips to the west coast were out of the question in 1940, this meant southern schools.

From 1938 to 1940 series with Florida, Auburn and Tulane put the Eagles on the southern football map and earned Cotton and Sugar Bowl bids. Ticket sales at Fenway Park rocketed, BC claimed a share of the 1940 national title, and Frank Leahy lost only one regular season game in two years. This record lifted him to the top of the candidate list for the head coaching job at his alma mater – Notre Dame.

The change in scheduling philosophy did not work so well for Lou Montgomery. In the 1940s southern schools still retained “Jim Crow” clauses with the NCAA that prohibited black athletes from taking part in any event involving their teams, regardless of venue. BC travelled to New Orleans to face Tulane in September 1939, but all four of the games against Auburn and Florida during his playing career took place in Boston. Lightnin’ Lou sat every minute of every one of those games out. He also suffered a loss of playing time in the preceeding weeks preceding as Leahy tested formations without him in the line up in preparation. The Eagles needed the work as Leahy’s offense clearly lost a step without Montgomery. The team’s only loss in 1939 came against an uninspiring Florida team that went on to finish 5-5-1. BC generated very few yards against the Gators and lost by the pitiful score of 7-0. Boston newspapers howled that Lightnin’ Lou would surely have proved the difference.

When the Eagles headed south for Dallas on December 26th 1939 Montgomery stood on the train car with the team and received personal applause from the large crowd. They knew he would not be going along. Before the train pulled off he stepped off the team car and watched as the Eagles went to face Clemson without him.

BC lost a narrow contest 6-3. Sportswriters noted the strong line play on both sides and the shortage of vertical running yards. O’Rourke’s passing attracted attention as he threw both downfield and laterally. But dropped passes and lack of speed hurt the Eagles. BC penetrated Clemson’s twenty yard line several times but even a first-and-goal with three minutes to play proved useless. The Tigers ground O'Rourke's drive to a halt.

When the team returned to Boston another large crowd met them at the station. Lou Montgomery rejoined his team and as he offered his encouragement and expressed pride in their effort someone shouted that BC would have won had he been allowed to play. He only shook his head with sadness and humility, saying:

“No. No, I don’t think so.”

“No. No, I don’t think so.”But privately doubts were stronger. That same day at the train station Leahy commented quietly to his little halfback

“Louis, if they had let us bring you along we wouldn’t have lost.”

Montgomery accepted the praise, replying:

“I’m always going to believe that, coach.”

Leahy never treated Montgomery poorly or expressed any personal racism. He was happy to have black athletes on his team and probably did believe Montgomery would have made the difference in Dallas. He may also have had good reasons for feeling that he could not change the racial climate. But it is certain that the coach did not feel inclined to push the limits of inclusion and make personal, professional or financial sacrifices on behalf of his mistreated player.

A 2002 article in the BC student paper, The Heights, entitled “Ahead of their time,” recounts the history of the university's first black athletes. The article takes a positive tone [as student newspapers probably should] and praises Boston College for having never excluded black athletes. This pride is at least partially valid. Montgomery always said that his teammates treated him well and even initially opposed the idea of benching him for southern racism. But they soon gave way, especially when he urged them not to sacrifice the greater good of the team on his count. But it seems unlikely that he would not have gladly accepted their support had the team stood firm.

A 2005 Boston College M.A. thesis by Kevin Gregg is less optimistic than The Heights. Gregg concludes that the administration sacrificed fundamental Jesuit principles of brotherhood, equality and poverty for money and prestige. Gregg also found that while Boston’s black newspapers launched scathing attacks on the administration’s cowardice and hypocrisy, the city’s white press only seemed to care when the Eagles lost a game because of Lou’s absence.

This sad disparity became quite clear in 1940 when “the team of destiny” put together an 11-0 season and claimed a share of BC football’s only ever national title. After a strong showing in 1939 Leahy was able to strengthen his team. The 1940 Eagles were bigger, stronger and faster. And they could win without Montgomery, thus removing any cause for protest from the Boston Globe.

.gif)

Lightnin’ Lou missed the team’s coming out voyage to New Orleans in September, when Leahy’s men knocked off southern power Tulane at home. Students at the Auburn Polytechnic Institute greased the rail lines running through their town, forcing BC’s train to stop and receive their applause for beating a hated rival. In the excitement no one really noticed the absence of a 160 lb halfback.

Montgomery did accompany the team to New Orleans for the 1941 Sugar Bowl. While his teammates prepared for their toughest test in Robert Neyland’s Tennessee Volunteers, he played for cash in a black college all-star game. They stayed sixty-miles ou

tside of the city, away from distractions. Montgomery roomed in the heart of the city and took full advantage of the nightlife. But there is no doubt that he would rather have been with the Eagles, going against the Vols as a fully included representative of Boston College.

tside of the city, away from distractions. Montgomery roomed in the heart of the city and took full advantage of the nightlife. But there is no doubt that he would rather have been with the Eagles, going against the Vols as a fully included representative of Boston College.Lightnin’ Lou had been a Massachusetts all-academic prep star in 1936. He chose to represent his home state at Boston College, even though several other significant schools including UCLA offered him a scholarship. The greatest indicator of Lou’s true feelings during his BC years is that in his later life he openly stated in interviews that he would not make the same choice if given a second chance. This must be the one thing no college football fan ever wants to hear from an alumnus of his beloved program.

It is, of course, impossible to know whether BC could have broken the color line in the Cotton or Sugar Bowl in the early 1940s. What is certain is that Penn State and Wallace Triplett succeeded in desegregating the Dallas game in 1948. The Pitt Panthers and Bobby Greer accomplished the same for New Orleans in 1956. These dates preceded the general integration of southern college football by many years. Neither of these landmarks occurred because people at SMU or Georgia Tech were happy to play against integrated opponents. Indeed, in December 1955 Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin attempted to stop the game from proceeding and pointed in desperation at civil unrest surrounding a month-old bus boycott in nearby Montgomery, Alabama.

SMU accepted Wally Triplett because they and the Cotton Bowl wanted the best available opponent and Penn State had already taken a public stand against the Jim Crow clause. They could either back down or find a lesser foe, sacrificing prestige and revenue. The 1955 Panthers likewise refused to accept a bowl invitation without the inclusion of Greer. Georgia Tech students marched on the state capitol and burned Griffin in effigy not because they wanted general desegregation and loved black people, but because they wanted to see their Yellow Jackets play the best team available.

Perhaps similar resolve from Boston College in 1940 would have achieved such success. Perhaps four bloody years of fighting European fascism were necessary before Americans in the south could stomach such changes, even at the cost of losing a good football game. We will never know. We can only say for certain that the story of Lou Montgomery is not a bright chapter in the history of either college football or Boston College.

(Sources: Kevin Gregg, Tackling Jim Crow – unpublished M.A. thesis, Boston College 2005; Boston Globe, Lou Montgomery; The Heights, Ahead of their time; Reid Oslin, Tales from the BC sideline; Mark Purcell, 1940 BC vs. Georgetown – CFHS newsletter; DMN, 1940 Cotton Bowl; Wiki, 1956 Sugar Bowl)

No comments:

Post a Comment