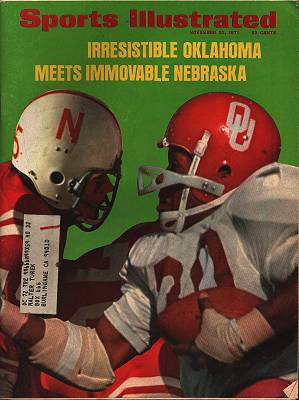

Dana Bible’s great Nebraska teams largely relied on good coaching of home-state farm boys. In the post-war era as television allowed the game to develop into an inter-regional phenomenon Devaney was able to restore Nebraska’s fortunes by developing national appeal and a recruiting network that spanned a continent. Wilkinson established a legacy in Norman of complete monopoly on in-state talent augmented with cross-border raids of the best Texas High School products. OU and Nebraska football developed into virtual mirror images. Both schools were flagship institutions in sparsely populated, geographically underwhelming football-mad states. Successive coaches at both programs found ways to attract the best players to their quiet towns, enabling them to field technically sound power-running teams characterized by under-stated class. College football evolved from the T and Diamond formations through the wishbone and into the option but one thing never changed. Every year Nebraska and Oklahoma lined up and ran at each other like a head-on train crash. The winner almost always took all.

In 1964 Bob Devaney received a phone call from an ambitious young coach whose three-year NFL career had ended two years earlier. A native Nebraskan and former state prep athlete of the year, Tom Osborne had played his collegiate football at his hometown Hastings College. He talked Devaney into giving him a position as an unpaid graduate assistant and started out coaching receivers in exchange for a dorm room and meals with the team. Osborne possessed a brilliant mind and in addition to pursuing his doctorate in educational psychology impressed Devaney as a coach sufficiently to earn the job as Nebraska offensive coordinator by 1967. Osborne possessed not only obvious tactical genius and profound organizational skills but also a rare personal touch. In 1969 he recruited Johnny Rodgers, a troubled young man from Omaha’s north side who had both been stabbed and shot another boy in the stomach before his sixteenth birthday. As a Nebraska freshman in 1970 Rodgers was involved in a gas station robbery that earned him two years probation. Osborne took responsibility for young man’s development and under his tutelage Rodgers stayed clear of trouble and played well enough to win the 1972 Heisman Trophy. Under Devaney Nebraska won consecutive national championships in 1970 and 1971. Osborne took over as head coach in 1973. The two men had successfully engineered a football revival in Lincoln. Most impressively they had done it without requiring a corresponding drop off in productivity from conference rival Oklahoma. In Devaney’s second championship year Chuck Fairbanks’ OU Sooners finished 2nd in the final AP poll. The two rivals played out a 35-31 Nebraska win in Norman that is widely considered to be ‘the game of the century’. Between 1970 and 1975 Oklahoma and Nebraska each won two national championships. Only once in those six seasons did either team finish outside the AP top ten [OU’s 20th place finish in 1970].

In 1964 Bob Devaney received a phone call from an ambitious young coach whose three-year NFL career had ended two years earlier. A native Nebraskan and former state prep athlete of the year, Tom Osborne had played his collegiate football at his hometown Hastings College. He talked Devaney into giving him a position as an unpaid graduate assistant and started out coaching receivers in exchange for a dorm room and meals with the team. Osborne possessed a brilliant mind and in addition to pursuing his doctorate in educational psychology impressed Devaney as a coach sufficiently to earn the job as Nebraska offensive coordinator by 1967. Osborne possessed not only obvious tactical genius and profound organizational skills but also a rare personal touch. In 1969 he recruited Johnny Rodgers, a troubled young man from Omaha’s north side who had both been stabbed and shot another boy in the stomach before his sixteenth birthday. As a Nebraska freshman in 1970 Rodgers was involved in a gas station robbery that earned him two years probation. Osborne took responsibility for young man’s development and under his tutelage Rodgers stayed clear of trouble and played well enough to win the 1972 Heisman Trophy. Under Devaney Nebraska won consecutive national championships in 1970 and 1971. Osborne took over as head coach in 1973. The two men had successfully engineered a football revival in Lincoln. Most impressively they had done it without requiring a corresponding drop off in productivity from conference rival Oklahoma. In Devaney’s second championship year Chuck Fairbanks’ OU Sooners finished 2nd in the final AP poll. The two rivals played out a 35-31 Nebraska win in Norman that is widely considered to be ‘the game of the century’. Between 1970 and 1975 Oklahoma and Nebraska each won two national championships. Only once in those six seasons did either team finish outside the AP top ten [OU’s 20th place finish in 1970].

The same year Osborne assumed command in Lincoln Oklahoma’s own long-standing assistant moved up to the head job in Norman. Barry Switzer, a cock-sure young Arkansas graduate, took over for Fairbanks who moved to the NFL. He set about installing a version of Darrel Royal’s new 'wishbone' offense and saw immediate success [even despite NCAA sanctions for transcript irregularities dating to Fairbanks’ tenure]. Switzer’s teams smashed national records for offensive output on the ground. His first Sooner team went 10-0-1 finishing in the AP poll behind only Woody Hayes’ Buckeyes and Ara Parseghian’s Fighting Irish. Switzer won his first five meetings with Osborne, including a1975 home date in which the unbeaten, second ranked Huskers suffered a 35-10 humiliation at the hands of a seventh ranked OU squad that had picked up an inexplicable loss to the visiting Kansas Jayhawks the preceding week. Osborne’s first five Nebraska teams were good. They were excellent, in fact. From 1973 to 1977 Nebraska went 4-1 in the post-season, including victories over Texas in the 1974 Cotton and Florida in the 1975 Sugar Bowl. But they were not good enough to beat OU.

When the Sooners travelled to Lincoln for Switzer and Osborne’s sixth meeting as head coaches on November 11th 1978 they were again ranked number one and standing unbeaten at 9-0. Behind the explosive running of junior halfback Billy Sims, who would claim Oklahoma’s third Heisman Trophy that year, the Sooners led the nation in rushing with a massive 415 yards per game. Overall, the fourth ranked Huskers were even more productive. Despite a 3-point performance in their season opening loss at eventual national champion Alabama, Nebraska was averaging 515 yards total offense and scoring 41.5 points a game. While neither team relied on vertical passing to any great degree the Huskers showed slightly more balance. Operating out of the Sooners' precision wishbone attack quarterback Thomas Lott was averaging less than seventy yards passing. His counterpart Tom Sorley was passing for 175 yards a game, which only helped Nebraska’s own impressive performances on the ground.

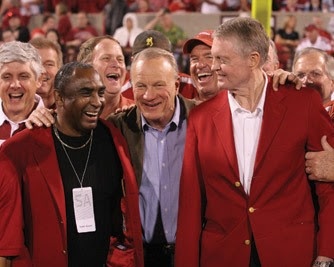

Johnny Rodgers, Barry Switzer and Tom Osborne in more recent times

During a joint mid-week press conference Osborne played some public mind-games, intentionally downplaying his team’s chances. He told reporters in Switzer’s hearing:

“We have good running backs. [Rick] Burns or [Isaiah] Hipp could contribute to their team, but we don’t have anyone they even recruited out of High School.”

Burns had been an overlooked running back out of Wichita Falls, while Hipp was a walk-on from rural Chapin, South Carolina. Despite leading his home-town Eagles to two state AA championships and amassing nearly 3,000 career yards Hipp was not recruited by any college due to a shoulder injury he suffered as a senior. As a High School freshman in 1971, Hipp had watched the OU-Nebraska game on television. Despite never having been near the state of Nebraska he decided on the spot that wanted to be like Johnny Rodgers and would only play for the Huskers. Without any prior contact with Osborne Hipp scraped the money together to fly to Lincoln. He enrolled at NU and managed to catch the coaching staff'’s attention in walk-on try outs. He broke out as redshirt sophomore in 1977 with several hundred yard games, including a 77-yard TD against Indiana that is still Nebraska’s longest scoring run. Hipp was typical of Osborne’s Cornhuskers. Nebraska coaches found talent from across the country, and sometimes talent found them. Osborne’s staff improved players as well as any program in the nation. He may have been serious in talking about his team as over-looked, under-talented and generally not good enough for Norman. But Osborne knew his I-formation offenses, alternating lightening tailbacks Hipp and Tim Wurth with bruising fullbacks Burns and Andra Franklin, could rack up points on anybody. Against Nebraska's prolific offense backed up by famed “black-shirt” defense and playing at home, even Barry Switzer’s Sooners would struggle.

Isaiah Moses Hipp, walk-on

Although the matchup pitted the nation’s two leading offenses both coaches predicted a defensive battle. They were exactly right. In typical fashion OU and Nebraska pounded each other at the line of scrimmage all day. Eventually the narrow margin of victory came from a few fumbles caused by the handful of crucial hits that somehow stood out amid a great host of punishing, text-book tackles.

Virtually nothing separated the teams. Nebraska outgained Oklahoma by only twenty-two yards, 361 to 339. OU ran the ball sixty-one times, Nebraska sixty-two. Oklahoma made only thirteen first downs to Nebraska’s eighteen, but as was characteristic of the wishbone the Sooners made longer runs and outgained the Huskers on the ground by nearly eighty yards and 1.5 yards per carry. OU drew first blood, reaching the end zone on their second possession. The Sooners drove twenty-six yards to the Nebraska forty-four before Billy Sims kick-started his monster day by skipping through the line over right tackle, shaking off a Husker defender at the NU thirty-five and disappearing for a score. Sims was on his way to a 153 yard, two touchdown day and for a moment it looked as though Nebraska would be out classed again. The Huskers followed OU’s score with a Berns fumble on his own thirteen yard line. Fortunately for Osborne the blackshirts responded. Nebraska stuffed OU and pushed them back a yard on the first two plays. On third-and-eleven Lott went around left end on a QB keeper only to meet linebacker Lee Kunz at the corner and have the ball mercilessly stripped. Kunz’ points-saving takeaway provided the first in a string of OU turnovers that defined the game.

The wishbone, like any option offense, can chew up plenty of clock and cover a lot of territory – sometimes quickly in big plays. But the system is one dimensional, and never more so than in Switzer’s version. Lott finished the day with telling passing statistics: zero completions on two attempts. Nebraska defenders knew what was coming and brought pressure consistently, flying to the ball. For success, the wishbone requires misdirection, superior blocking schemes, and above all, ball security. On Oklahoma’s next possession Lott led his team to the Nebraska forty-three before a busted pitch out gave up another turnover. The Sooners simply could not afford such mistakes, but they kept coming. OU put the ball on ground nine times and lost it six. Even the irrepressible Sims was not immune. He lost two fumbles, including one at the Nebraska three yard line in the final minutes of the game with only a field goal separating the two sides. After the game a dejected Sims refused to cut himself any slack, telling reporters:

The wishbone, like any option offense, can chew up plenty of clock and cover a lot of territory – sometimes quickly in big plays. But the system is one dimensional, and never more so than in Switzer’s version. Lott finished the day with telling passing statistics: zero completions on two attempts. Nebraska defenders knew what was coming and brought pressure consistently, flying to the ball. For success, the wishbone requires misdirection, superior blocking schemes, and above all, ball security. On Oklahoma’s next possession Lott led his team to the Nebraska forty-three before a busted pitch out gave up another turnover. The Sooners simply could not afford such mistakes, but they kept coming. OU put the ball on ground nine times and lost it six. Even the irrepressible Sims was not immune. He lost two fumbles, including one at the Nebraska three yard line in the final minutes of the game with only a field goal separating the two sides. After the game a dejected Sims refused to cut himself any slack, telling reporters:

“I just got hit. But it was carelessness, not the hit. I don’t think I played a good game at all.”

Sims did play a good game. Running backs didn’t gain 150 yards with two scores against Nebraska on poor performances. Not with Osborne running the show. Sims lost the ball because of the hit. OU kept losing the ball all day because everywhere they turned there was a Husker waiting with a hit.

Nebraska answered OU’s relentless ground game with slightly more in the way of balance and variety. After the Sooner’s second turnover Nebraska took the ball fifty-seven yards the other way on a drive that including a ten-yard pace run from Hipp, a deep ball from Sorley to receiver Junior Miller, and a sideline flare pass that Burns converted to a first-and-goal at the OU nine. The drive finished with a straight up power run from Burns out of a deep set I. Nebraska had found their rhythm and very nearly scored again seconds before the break after forcing a David Overstreet fumble on Oklahoma’s own twenty-eight. On that occasion the OU defense limited the damage and Nebraska kicker Billy Todd found only the right upright from twenty-one yards. But even with the score tied and the Huskers’ finishing the half on the disappointment of a botched field goal, it was clear which team possessed the momentum.

The second half picked up exactly where the first had left. Overstreet lost a second fumble on exactly the half way line following a crushing hit from Nebraska’s Derrie Nelson. After OU held the Huskers to nothing on two plays Sorley went deep to Miller again, this time for a thirty-three yard gain. The Nebraska quarterback finished the day with a competent 111 yards on 8 of 20 attempts. That was 111 crucial passing yards more than Oklahoma managed. From third-and-ten Nebraska might have let another turnover slip without converting to points, but Osborne’s power-running offense was backed up by just enough aerial proficiency to keep his team on the field. Four plays took Nebraska the remaining distance with Hipp deftly evading tackles on a quick-footed scoring run from eight yards out.

Nebraska had a precious 14-7 lead but Oklahoma answered immediately. The Sooners drove seventy-three yards on the next possession, showing what they might have done had they been able to protect the football more consistently. Sims capped the march with a thirty yard touchdown run, bursting over the right end of the line before reaching the end zone untouched. For once on the afternoon a Sooner back made a big play without taking a hit or having to physically break a tackle. That would be the last time. On a fifty yard march beginning late in third quarter Sorley brought Nebraska back inside the Sooner ten with a first-and-goal before finally settling for another short field goal attempt from Todd. On his second try the Husker specialist finished the job. Nebraska had a three point lead. Ten minutes later when Sims lost the ball for Oklahoma’s sixth and final time after OU had once again ground their way into scoring position, Osborne finally had his win over Switzer.

The two coaches went head-to-head a total of seventeen times with Switzer earning a clear advantage 12-5. Neither man ever coached at another school. Both achieved astounding success despite sharing a tiny conference with an equally weighted powerhouse rival. Switzer coached at OU until 1988going 157-29-4 with two national titles and at least a share of twelve conference championships. Osborne stayed at Nebraska for a quarter century, eventually surpassing even Bud Wilkinson’s Big Eight win tally with a career record of 255-49-3. He earned three national titles and at least a share of thirteen conference championships. As both assistants and head coaches the tenures of Barry Switzer and Tom Osborne provided the golden age of a rivalry that defined college football on the plains of Middle America for more than half a century.

The defining play of the greatest college game ever played

(Sources: SI, Hipp: Wonder walk-on; AP poll archive; cfbdatawarehouse.com; College football’s 25 greatest teams; Great college football coaches; Fort Worth Star-Telegram)

Can I get a block in the back, please?!

ReplyDelete~Josh

Yes. I had considered adding a note to the effect that OU fans still maintain the play should have been called back. Refusal to forgive or forget is, I maintain, essential to the spirit of the game.

ReplyDelete